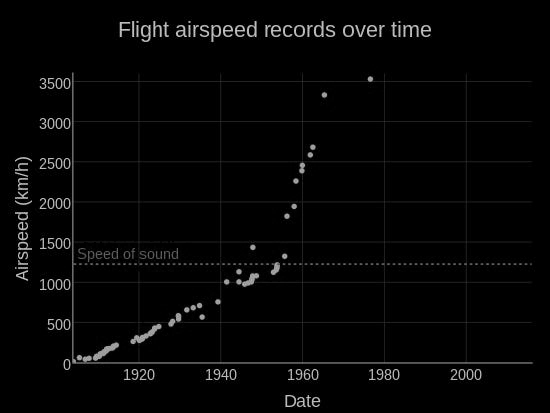

The current world shares many similarities with the world of the 1990s. In particular with regards to heavy industries, manufacturing methods, and factories, while there has been a marginal increase in automation in some countries. The same can be said for transportation, as the cars, planes, and trains we currently use have seen little innovation in the past three decades. The most commonly used airplanes in the world, such as the Airbus A320, date back to the 90s. Performance-wise, for example, airplanes have ceased to improve their speed since the 1970s, due to the fiatisation of the economy. As energy costs have become increasingly expensive, as seen in the 1972 oil crisis, innovation efforts have primarily focused on energy efficiency. The main difference between the Airbus A330 and A330neo is a 12% to 15% reduction in fuel consumption rather than improvement in the aircraft velocity, passengers capacity, etc.

Communication technologies have undergone significant changes with the advent of the Internet, which has largely replaced radio, television, and newspapers. The impact of the Internet on society should not be underestimated, but it should not be overestimated either. It should rather be classified as it is: within the realm of social and cultural innovation rather than purely technical innovation, in the sense that it has not had a direct impact on our daily lives. The Internet itself does not introduce new methods of production, like the shovel, steam engine, or robotics, but it provides a framework for exchanging information that can lead to innovation or a paradigm shift, such as mail or coffee shops. The true technology of the Internet lies in data centers, transcontinental cables (which have existed since the 19th century with telegraphs), and human-machine interfaces.

An adult living in 1964, during a time of the early stages of color television and globalization fueled by container ships and airplanes, would be much more bewildered when transported to the 1990s than an adult in 2021 sent back to the 1990s. The 1960s witnessed the emergence of electronic music, with elektronische musik in Germany and the work of Pierre Schaeffer's Studio d'Essai in France, which led to musique concrète, the precursor to sampling, and various genres of music thereafter, such as ambient music. Brian Eno and Aphex Twin would be among the greatest contributors to electronic and ambient music, with their respective releases of Ambient 4: On Land in 1982 and Selected Ambient Works 85-92 in 1992. These albums are undoubtedly some of the most innovative and musically significant of the previous century.

In parallel, blues rock evolved into hard rock in the 1960s, which then led to the golden age of metal with bands like Slayer, Anthrax, and Megadeth. This, in turn, gave rise to projects in death metal (Death) or black metal with bands like Mayhem or Burzum – a prominent figure in dark ambient music. It was also the emergence of minimalist music with artists like La Monte Young, Steve Reich, and Philip Glass. Western classical music continued its development, with electro-acoustic music deconstructing the traditionally associated codes and structures of music (as exemplified by John Cage's famous piece 4'33"). One of its well-known variations is noise music, which takes a different approach from electro-acoustic music, emphasizing a subtractive rather than additive approach. This gave rise to scenes like Japanoise in Japan, a significant cultural influence on extreme Japanese cyberpunk (e.g., Crazy Thunder Road (1980), Akira (1988)), as well as industrial and post-industrial music (Current 93, Coil), which are prominent names in Western experimental music.

In less than 50 years, the music scene has been profoundly disrupted, whether through the emergence of modular synthesizers or the development of more conventional genres like rock or jazz. There is still much to be said about music in the second half of the 20th century, such as the punk scene, for example. In a broader sense, the music of the late 1990s, like UK garage, is quite distinct from the music of the early 1960s, like progressive rock. However, the music of the late 1990s and the early 2020s remains relatively close in terms of codes, structure, and values.

HIndeed, artists like Tupac and music groups like Nirvana remain relatively popular despite the couple of decades that separate us from their heyday. What were the technical musical innovations between that era and ours? Relatively few. The only one that comes to mind is the development of generative adversarial networks (GANs), which could bring a revolution in the way we listen to music. Similarly, the emergence of the Internet and smartphones has changed our way of consuming music, with Walkmans giving way to iPods and then smartphones. The music industry has retreated in the face of the rise of streaming services like YouTube and Spotify. However, everything associated with music in 2023 seems to be a relic of the 1990s, like a cultural ghost haunting us. Vinyl records are making a comeback, G*59 is producing cassettes, there's a return to a Y2K aesthetic, and old-school rap and R&B can be seen as part of a cyclical conception of cultural development.

This concept of cyclical culture is not new. Several cultural theorists, such as Ibn Khaldun or Carlyle, had already put forth the idea of a dialectical process in a cultural context. There is also little doubt that the 1990s drew inspiration from the generations that preceded them, such as the contrast between the pop culture of the 1980s and the emphasis on individualism and identity that followed in the 1990s. However, each cycle has brought with it its share of innovation, at times quite significant, but it seems that innovation has stagnated for the past three decades.

To better understand this phenomenon, it would be relevant to connect it to Mark Fisher's concept of hauntology.

'The ghost as a cipher of iteration is particularly suggestive. At the beginning of Specters of Marx, Derrida talks about the way in which the anticipated return of the ghost may be mobilized on behalf of a deconstruction of all historicisms that are grounded in a rigid sense of chronology. 'Haunting is historical, to be sure', he writes, 'but it is not dated, it is never docilely given a date in the chain of presents, day after day, according to the instituted order of the calendar.' The question of the revenant neatly encapsulates deconstructive concerns about the impossibility of conceptually solidifying the past. Ghosts arrive from the past and appear in the present. However, the ghost cannot be properly said to belong to the past, even if the apparition represents someone who has been dead for many centuries, for the simple reason that a ghost is clearly not the same thing as the person who shares its proper name. Does then the 'historical' person who is identified with the ghost properly belong to the present? Surely not, as the idea of a return from death fractures all traditional conceptions of temporality. The temporality to which the ghost is subject is therefore paradoxical, as at once they 'return' and make their apparitional debut. Derrida has been pleased to term this dual movement of return and inauguration a 'hauntology', a coinage that suggests a spectrally deferred non- origin within grounding metaphysical terms such as history and identity.'

Hauntology can be summarized, in a few sentences, as the persistence of cultural elements from the past, akin to a ghost haunting a subject. While this term was coined by the French philosopher Jacques Derrida in his book Spectres of Marx (1993), within a specific post-Marxist context, it was primarily reappropriated by cultural theorist Mark Fisher. Fisher describes hauntology as a nostalgia for lost futures, intertwining it with elements of cultural memory, retro-aesthetics, temporal disjunction, and the persistence of the past.

Indeed, hauntology as an artistic genre has been primarily associated with music, particularly with British electronic musicians of the early 2000s. Artists like William Basinski with his Disintegration Loops, The Caretaker, and Burial's album Untrue are often cited as notable examples of hauntological music. These artists create soundscapes that evoke a sense of nostalgia, decay, and a haunting presence of the past. Their works incorporate elements of fragmented memories, distorted samples, and a spectral atmosphere that embodies the concept of hauntology in an auditory form.

“The short-lived spate of interviews he did around Untrue teem with references to uncanny presences, subliminal hums, moments when you glance at the face of a friend or family member and catch something alien in their expression. Burial even enthused about his childhood love of the ghost stories of M.R. James, one of those gentlemen occultist writers who are touchstones for the UK hauntologists.”

…” Interviewed by the late British critic Mark Fisher, Burial spoke of creepy epiphanies he’d experienced walking through deserted night-time areas of London: “Sometimes you get that feeling like a ghost touched your heart, like someone walks with you.” Song titles like “Archangel” and “Feral Witchchild” suggest superstitious thinking, or at least an openness to the idea that there are supernatural dimensions, other realms that leak through into our reality in the form of visions or unsettling sensations.”

These musicians aim to evoke cultural memory and the aesthetics of the past, drawing, for example, from British cultural sources of the post-war era through sampling, as done by The Caretaker, particularly in projects like An Empty Bliss Beyond This World and Everywhere at the End of Time. In fact, in 2017, he released an album titled Take Care, It's a Desert Out There... as a tribute to Mark Fisher, who died by suicide in the same year. Fisher played a major role in shaping The Caretaker's sound. He identifies the crackling of vinyl as the main sonic signature of hauntology, which makes us aware that we are listening to a sound that is not in harmony with our temporality, signaling the return of a certain sense of loss that invokes the past and marks our distance from it.

Fisher connects The Caretaker's music to his broader project of describing capitalist realism - the political idea that not only has the future not arrived, but it no longer seems possible, and the melancholy of hauntology to the horizons closed off by capitalism.

The cultural landscape we find ourselves in leads us to constantly recycle the same cultural artifacts, as they dissolve within cultural memory. According to Fisher, we can no longer create something truly new; we can only imitate the past in order to give it a new form without truly moving beyond it. He particularly blames this as a characteristic of the late stage of capitalism: the deterritorialization of creativity by capital, feeding on itself due to a lack of means to expand.

While I don't fully endorse this analysis, it is evident that we have entered a cultural loop: we ended the 2000s decade with the first Avatar and Modern Warfare 2, and we are starting the 2020s decade with Avatar 2 and Modern Warfare II, the remake – which itself received a remastered edition two years prior, a trend that was extremely common during the eighth generation of consoles (2014-2020). The most popular music on TikTok, the currently popular social media platform, consists mainly of R&B songs from the late 2000s or sped-up versions of those songs, reminiscent of the nightcore wave from that era. There is a strong nostalgic sentiment for the 2000s, with the revival of Y2K style since the early 2020s.

Y2K confirms all the darkside prophecies of Marx, Wiener and McLuhan, all of whom saw that, far from being a relation between tools and their users, machine culture involves human and technical components in a total mesh. Here, 'technology' – if such a reification makes sense anymore – is not a tool, it is an environment. And it seems that we are only now coming to fitful awareness of that environment because of Mbug. The shadow showing up the diseased organ. Any attempt to think through the potential limits of Mbug infection is also, effectively, an attempt to map human dependence upon the technical environment. The more humans take computers – and computerisation – for granted, the more they are dependent upon them. In a prescient parable, McLuhan said that the one thing fish don't see is water, just as the one thing humans are unaware of is the technical environment from which they are increasingly inextricable. Now, as the hunt to find and eliminate potential carriers of Mbug is well underway, human beings, like fish forewarned of a viral infection in the water supply, are beginning to be aware of the extent of their immersion in the electrocybernetic Matrix.

HY2K is not only everywhere computers are, but it is also everywhere silicon chips are: it is a molecular bug, infecting even the tiniest interstices of the technical environment, an invisible invader into technical systems that have themselves tended to shrink out of human sight. It is a global problem that can only be tackled locally. Even if, say, airlines do manage to root out all their Mbug infections, they are still dependent upon agencies who may not have been so successful in debugging their systems. So Y2K is not so much a catastrophe as a hypercatastrophe. Y2K-os can be extrapolated from any number of contingencies and their potential interexcitations: traffic failure, food shortages, ATM malfunction, stock market crashes, exchange of nuclear weapons – anything that is dependent upon chips is potentially infected with Mbug. Which is bad news for us, who are symbiotically intertwined with them.

Y2K aesthetic refers to the visual and cultural style associated with the approach of the year 2000. It is characterized by nostalgia for the end of the 20th century and fear of the unknown future. It often includes elements such as neon lights, futuristic technology, and vibrant colors. This aesthetic can be found in fashion, design, and pop culture of the 1990s and early 2000s, with a particular focus on the intersection of nostalgia and futurism.

One of the distinctive features of the Y2K aesthetic is the prominent use of chrome as the most emblematic material in this niche. It was widely used at the turn of the 21st century, from reflective materials to futuristic concepts, as an elegant way to convey a futuristic aesthetic. The globular aspect, gradients, thick lines, and uncompromising minimalism are also characteristic of the genre. Glacier blue and vibrant orange are commonly used in conjunction with each other, with the former evoking the freshness and undefined form of the upcoming digital era, while the latter recalls cities, urban aesthetics, cones, and road signs. These colors are popular in the current neo-Y2K revival in fashion and graphic design. The iMac G3 monitor also holds significant influence, from its iconic "Bondi blue" color to its use of transparent plastic and other common materials of that time.

Art, video games, and music, in particular, play significant roles in this niche. It has long been associated with the graphics of the PS2, with games like Virtua Fighter, Rez, or Wipeout. Jungle and drum and bass music were also quite popular in the underground rave culture of the 1990s, conveying a message of novelty, dynamism, and openness to the cyber future.

Today, the neo-Y2K revival is associated with R&B music, featuring artists like Justin Timberlake and Nelly Furtado, as well as producers like Timbaland, who dominated the music industry in the late 2000s. However, I consider this to be a distinct and separate niche that covers a specific ethos in the post-Y2K era, marked by the rise of connectivity, post-MySpace social media, and the 2008 financial crisis and its consequences. This era is also shared with "chick flick" films, commonly associated with the transition to the year 2000.

A trend that is prevalent in the contemporary gaming world is the "demake" trend, which highlights a return to aesthetic codes of the fifth generation of consoles, with games like Silent Hill (1999) while sometimes retaining certain gameplay mechanics specific to that era or adapting them with the advancements that led to contemporary game design.

For example, the trend of retro FPS (or boomer shooter) has gained momentum since 2016, with games like Dusk (2018), Amid Evil (2018), Ultrakill (2021), or games by New Blood in general. These games draw much of their inspiration from early FPS games such as Doom (1993), Wolfenstein 3D, Quake, Unreal Tournament, or Duke Nukem 3D, featuring intense gameplay, significant maneuverability, and a large number of enemies (sometimes consisting of simple frames, as seen in Nightmare Reaper). This contrasts greatly with mainstream FPS games of the 2010s, which focused more on immersion, realism, and grounded gameplay, such as the Call of Duty, Battlefield, and Medal of Honor franchises in the early 2010s, as well as competitive games like Rainbow Six: Siege or Overwatch in the later years. This deconstruction of the genre is partly a reaction against the policies adopted by major game publishers, emphasizing multiplayer games with skill-based matchmaking (SSBM) that provide maximum player retention, with an emphasis on microtransactions, cosmetics, battle passes, and other profit-oriented decisions at the expense of individual gameplay experience.

The 2000s are also associated with the golden age of massively multiplayer online games (MMORPGs) such as Dofus (2004), which experienced a resurgence driven by the community, as well as World of Warcraft (2004), which, with the release of its Classic expansion, reached user numbers comparable to its peak. Other virtual worlds like worlds.com (1995), Habbo (2000), or Second Life (2003) also played a role and inspired projects like VRChat (2014) and the whole metaverse trend that began in the early 2020s, including Decentraland (2020), and others. This era was also favorable for the emergence of online fashion games that remain multiplayer but focus on individual experiences. Examples include Moviestarlanet, Stardollz, Mabimbo, Sailor Fuku, Gaia, which highlight self-expression through fashion and fantasy. Thus, we have seen the emergence of games like Everskies (2020) that incorporate and expand on these concepts by offering more customization.

Furthermore, there are several trends within Internet subculture that explicitly draw inspiration from past works and cultural productions. For example, there is a cult following that has developed around video games, sometimes well-known ones like Silent Hill 2 (2001), Metal Gear Solid 2 (2001), or more recently Spec Ops: The Line (2013), and sometimes more niche titles like Earthbound (1994), Yume Nikki (2004), and Runescape (2001). This trend is not limited to video games alone; one can think of the music group Fishmans, which experienced a resurgence in popularity towards the end of the 2010s, mainly through image boards like 4chan, as well as anime series like Serial Experiment Lain, which is at the heart of the post-2016 internet accelerationist aesthetic.

This aesthetic resurgence of the 2000s is not necessarily observed in current musical productions, which today are mainly composed of phonk, drill, independent rock sounds, and other mainstream genres. However, there is a sub-niche of music called breakcore that draws a lot of inspiration from late '90s electronic music, such as drum and bass, UK jungle, and other rave music genres that conveyed messages of rebellion and optimism about the future.

Interestingly, TikTok, as well as the Reels format more broadly, is strongly associated with the revival of Y2K aesthetics in music. The use of R&B music characteristic of the late 2000s with artists like Timbaland, Justin Timberlake, and Nelly Furtado was one of the catalysts for the neo-Y2K revival, as I call it. These songs are relatively upbeat, high-tempo, and dance-friendly, contrasting with the emo-rap music of the late 2010s by artists like Billie Eilish or Soundcloud rappers like Lil Peep or XXXTentacion, which are slower and more personal in their approach. This can be complemented by the trend of speeded-up versions reminiscent of the nightcore remixes of the 2010s, contrasting with the slowed and reverb versions that were also characteristic of the end of the previous decade. This could also indicate certain significant cultural shifts, such as a transition from a more collective and impersonal culture to the next. This would align with cycles like grunge and post-grunge, where bands like Nirvana paved the way for R&B music.

However, all of this does not mean that our video game, film, or music codes are rooted solely in nostalgia for the past. As mentioned earlier, the biggest games still strive to be innovative in their approach, as seen with the explosion of battle royale games following the success of Fortnite (2018). Among the most popular films at the moment, we have the Marvel films and the MCU, which have been emulated, albeit without much success, by other studios, with Warner's DCEU being a prominent example. But it is important to highlight the underlying quantitative variation: among Disney's biggest contemporary successes, there are many live-action films or remakes like The Lion King (2021). The video game industry also experienced an era of remakes during the eighth console generation, with remastered versions of cult games from the seventh generation, such as the Assassin's Creed, Bioshock, and Uncharted franchises.

This has partly affected the console's potential to release new IPs, encouraging developers and publishers to capitalize on players' nostalgia and the lack of experience of new players at a lower cost. Between 2014 and 2016, the console only had three major exclusives in the form of Killzone: Shadow Fall (2014), Bloodborne (2015), and Uncharted 4: A Thief's End (2016), compared to around ten for the first two years of the PlayStation 3's lifespan, including games like Killzone 2 (2008), Resistance: Fall of Man (2007), Resistance 2 (2009), Motorstorm (2006) and Pacific Rift (2008), Gran Turismo 5 (2009), Little Big Planet (2008), inFamous (2009), Uncharted 1 (2007), and 2 (2009), among others.

The first game to release on the PlayStation 5, the ninth console generation, was a remake of Demon's Souls, originally released in 2008 on the PlayStation 3, a console that still suffers from a lack of games and exclusivity. However, this is tied to various factors such as the 2020-2021 semiconductor crisis, as well as the economic and industrial consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, which have impacted manufacturing capacities, maritime transport, and so on. Many PlayStation 4 games were later updated for the next-gen console, with patches improving performance, but most notably graphics, such as Horizon: Zero Dawn (2018), Uncharted 4 (2016), etc., artificially filling the gap of native video games for the console.

The main themes of Y2K aesthetics are nostalgia for the early days of the internet and technology, a futuristic and technology-focused aesthetic, and a blend of fashion and design elements from the late 1990s and early 2000s. However, it seems that this has been partly abandoned, as cultural deterritorialization does not inherently include the essence of these niches. Technology now plays either a neutral or negative role, which contrasts greatly with the techno-optimism of that era. The metaverse seems to be more of a corporatist dystopia than an innovative or liberating technology.

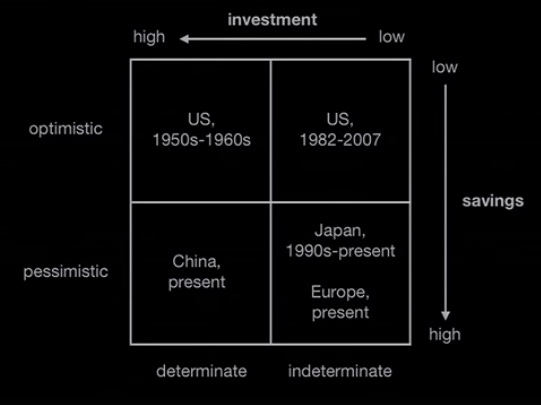

Nostalgia is therefore a recurring theme in the post-Y2K world. Unable to imagine a future, people retreat into idealized versions of the past - one that still allowed us to dream and conceive a vision of the world beyond contemporary social and cultural limitations. The future is for many undefined - which is important to distinguish from having a pessimistic view of the future, which is defined materially by the degree of investment one can put into it. This is reminiscent of Peter Thiel's concept of an optimistic/pessimistic and determinate/indeterminate future, developed in his book "Zero to One" (2014)

Thiel distinguishes an ambivalence between the ability to invest and the ability to save: it is a representation of the concept of time preference, as described by Carl Menger. The more uncertain the future, the less encouraged we are to invest, and the more unfavorable our idea of the future seems, the more encouraged we are to save. Fiat currency distorts this perception by devaluing savings, thus encouraging constant consumption. The nature of consumerism is therefore to spend everything as soon as possible, as the problems of tomorrow will be those of future generations.

Cyberpunk, for example, was born in the United States in the 1970s, through the new wave of science fiction. Authors like William Gibson, with the famous Neuromancer, inspired a whole generation of writers and filmmakers to explore the concept of a high-tech, low-life world and everything that comes with it: neo-noir dystopia, corporate espionage, mass surveillance, post-humanity, cybernetics, and more. Beyond being works of fiction, it is also the exploration of relevant themes of that time, with growing technological advancements that challenged the relationship between the body, the individual, society, and technology. What happens when metaphysics are sacrificed for flying cars and what we end up with are tracking chips signed by big corporations? This is even more evident when we look at the Japanese sub-branch of cyberpunk, also known as extreme Japanese cyberpunk, which focuses on showcasing the social consequences of the rapid transition to a post-industrial society, as was the case in Japan during the 1970s.

This cultural production was fueled by a defined vision of the future, the exploration of ideas when pushed to their ultimate consequences. What happens when the future is no longer defined, as is the case in the Western world and the world at large today? Then, it becomes impossible to project ourselves into it, to imagine the consequences of technological and social development on humans, the impact of these changes, and how we could react to them. However, it's not as if we are spared from all the issues: for example, climate change is a topic that is under-addressed culturally, despite being the most popular issue among Zoomers, a generation that is much more politically engaged than average, surpassing concerns about the state of the economy or issues such as security or immigration. This highlights the existential role that this theme plays in this cultural imaginary.

Indeed, I would be unable to name a mainstream or experimental film that deals with a world post-major climate change. What would be the cause? What would be the consequences? What solutions would have been implemented? In the most optimistic versions, we could imagine that nuclear power, geothermal energy, or renewable energies would have been the solutions leading us towards solarpunk ideals. Perhaps even the world would have survived and thrived through the use of fossil fuels, but we are talking about fiction after all. Or, in a more dystopian version, there would be major social and technological changes. Could we re-industrialize after depleting all accessible fossil fuels? Would the energy transition be a great failure if it is not accompanied by larger social change? These are scenarios that would be interesting to explore.

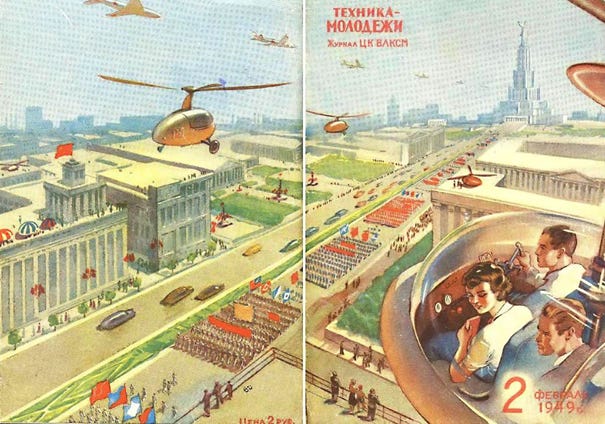

More broadly, while the Soviets could dream of underground cities and flying cars in the 1950s, and Americans dreamed of space conquest in the 1970s, Westerners today struggle much more to imagine what the United States or Europe could look like by 2050. The stability of our way of life is not even guaranteed, and it wouldn't be foolish to speculate that political regimes in place may no longer be relevant by then, such as the growing anti-monarchist sentiment in the United Kingdom, which may struggle to maintain its legitimacy after the death of Elizabeth II.

There may be an exception to these generalizations, which are endemic to the West. Indeed, a country like China is a living actor in contemporary geopolitics and has succeeded under the leadership of the CCP in lifting the country from a century of humiliation and becoming a leader in military, industrial, energy, and other fields. The Chinese have a vision of a bright future. In fact, they are the only ones with a more positive outlook on the future in a post-COVID context than pre-COVID. China is now a dynamic and future-oriented country. They aim to implement socialism by 2035 and reunify Taiwan by 2049, the centennial of the civil war.

Sinofuturism, or Chinese futurism, is a fascinating movement primarily theorized by Lawrence Lek, and his friend Steve Goodman, also known as kode9, has extensively discussed the subject. I invite you to watch the eponymous film, which explores the evolution of Chinese thought from 1839 to 2016 and speculates on its development up to 2046.

“Sinofuturism is an invisible movement. A spectre already embedded into a trillion industrial products, a billion individuals, and a million veiled narratives. It is a movement, not based on individuals, but on multiple overlapping flows. Flows of populations, of products, and of processes. Because Sinofuturism has arisen without conscious intention or authorship, it is often mistaken for contemporary China. But it is not. It is a science fiction that already exists.”

The poststructuralist philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari highlighted that capitalism undergoes processes of deterritorialization and reterritorialization, which means that capitalism destroys old institutions but also generates new boundaries, barriers, and limits in the process. Nick Land later appropriated this concept to assert that 'Neo China comes from the future' in his essay Meltdown, aiming to emphasize the idea that capitalism, as a process, used the Western world through globalization, the age of exploration, liberalism, etc., to develop. By deterritorializing itself, capitalism found a new host in China to reterritorialize: the China of Deng Xiaoping represents the new form of techno-capitalism that is no longer exclusive to the West but has indeed become a global trend.

The story goes like this: Earth is captured by a technocapital singularity as renaissance rationalitization and oceanic navigation lock into commoditization take-off. Logistically accelerating techno-economic interactivity crumbles social order in auto-sophisticating machine runaway. As markets learn to manufacture intelligence, politics modernizes, upgrades paranoia, and tries to get a grip.

The body count climbs through a series of globewars. Emergent Planetary Commercium trashes the Holy Roman Empire, the Napoleonic Continental System, the Second and Third Reich, and the Soviet International, cranking-up world disorder through compressing phases. Deregulation and the state arms-race each other into cyberspace.

By the time soft-engineering slithers out of its box into yours, human security is lurching into crisis. Cloning, lateral genodata transfer, transversal replication, and cyberotics, flood in amongst a relapse onto bacterial sex.

Neo-China arrives from the future.

Hypersynthetic drugs click into digital voodoo.

Workers are now being replaced by machines, and culture is increasingly merging with the economy. While China continues its growth and economic liberalization, the West is sinking into nationalism, conservatism, neopaganism, humanism, progressivism, or Marxism. Riddled with guilt inherited from Christianity, the West turns against itself. As the West loses control over international trade hubs in favor of the East, Western countries turn to protectionism. The welfare state erodes, domestic inequalities widen, and Western political systems are on the verge of collapse. New anti-authoritarian movements emerge everywhere to put an end to the decomposing neo-despotism.

In this context, sinofuturism lies at the intersection of reality and fiction. Singapore and Hong Kong have been the main sources of inspiration for cyberpunk environments, from Blade Runner (1982) to Ghost in the Shell (1995). Although science fiction has historically been prohibited in communist China, many authors have conceptualized futuristic stories and settings with Sino-Chinese values.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has significantly relaxed its restrictions over time and wishes to use media, primarily cinema, to instill a set of values in young Chinese people that align with its material needs to create the future it desires. In a document published in April 2020, the CCP elaborates on how science fiction, in particular, aligns with the party's ideological and technological objectives, which revolve around space exploration, artificial intelligence, robotics, electronics, automation, and nuclear technology. Emphasis is placed on developing a high-level film industry and sino-science fiction with advanced technical production capabilities. Films like The Wandering Earth (流浪地球, 2019) and Moon Man (独行月球, 2022) come to mind, both dealing with space travel. The former, being slightly better than the latter, became the third highest-grossing film of all time in the countr

These films must also incorporate Xi Jinping Thought, which represents a set of thoughts and policies specific to the current President of China, as well as depict and valorize Chinese values inherited from Chinese culture and aesthetics. They should cultivate technical innovation and promote scientific thinking. Therefore, the films should present China in a positive light as a technologically advanced nation capable of colonizing Mars or developing nuclear fusion, for example. The document also mentions the need for technological self-sufficiency by developing indigenous technologies and expertise.

The document emphasizes the lack of innovative ideas and scenarios, which hampers the country's cultural productivity. It suggests encouraging idea generation through festivals, creating specialized departments for each medium in universities, and so on. However, China is home to many talented authors. Liu Cixin and his Three-Body Problem trilogy come to mind, which has been a recent major success in hard science fiction.

The underlying idea throughout all this is the existence of alternative visions of the future, which can vary depending on the historical, cultural, social, and technological context of each society. This applies not only to China but to futurisms worldwide, such as Afrofuturism, Gulf futurism, transhumanism, and others. The difference lies in the ability to influence their environment culturally or economically, an area in which the CCP excels. However, all these visions are based on tenets of liberal humanism, such as the belief that technology can save the planet.

A purely peer-to-peer version of electronic cash would allow online payments to be sent directly from one party to another without going through a financial institution. Digital signatures provide part of the solution, but the main benefits are lost if a trusted third party is still required to prevent double-spending. We propose a solution to the double-spending problem using a peer-to-peer network. The network timestamps transactions by hashing them into an ongoing chain of hash-based proof-of-work, forming a record that cannot be changed without redoing the proof-of-work. The longest chain not only serves as proof of the sequence of events witnessed, but proof that it came from the largest pool of CPU power. As long as a majority of CPU power is controlled by nodes that are not cooperating to attack the network, they'll generate the longest chain and outpace attackers. The network itself requires minimal structure. Messages are broadcast on a best effort basis, and nodes can leave and rejoin the network at will, accepting the longest proof-of-work chain as proof of what happened while they were gone.

Bitcoin is a decentralized and trustless digital currency released as open-source software in 2009 by an individual or group of pseudonymous individuals known as Satoshi Nakamoto. This currency can be sent directly from one address to another in a peer-to-peer fashion through the Bitcoin network. Transactions are verified by nodes and recorded in a distributed ledger, also known as the blockchain. The ingenuity of Bitcoin lies in the use of cryptography to solve a well-known problem in distributed computing known as the Byzantine Generals' Problem—how to coordinate a distributed network while preventing it from being sabotaged by malicious elements.

Through the use of proof-of-work, Bitcoin introduces digital scarcity, which has paved the way for various applications of blockchain technology, such as Ethereum in 2014, which implemented smart contracts and NFTs. Several projects have been built on the Bitcoin network to enhance its capabilities, such as the Layer 2 Lightning Network, which optimizes transactions by reducing their footprint on a block and lowering transaction costs. However, several alternative cryptocurrency projects have also emerged to compete with Bitcoin. The Bitcoin paradigm of hard money aligns with various ideological and economic schools of thought, ranging from the Austrian School to Islamic economics.

Among the most influential readings on Bitcoin are "The Crypto-Anarchist Manifesto" (1988) and "The Cyphernomicon" (1994) by Tim May, "Shelling Out" (2002) by Nick Szabo, "b-money: an anonymous, distributed electronic cash system" by Wei Dai (1998), and, of course, Satoshi's whitepaper, "Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System" (2009).

Currently, my greatest concern regarding Bitcoin is not of a technical nature but rather a cultural one. Bitcoin, to some extent, lacks an appropriate culture. Memetics is a powerful tool for community building, and while many memes have emerged from the community, such as HODL or laser eyes, the lack of native crypto-thinkers or crypto-artists embodying hyperbitcoinization and the ethics of Bitcoin is evident.

Some Bitcoiners advocates speak of hyperbitcoinization, envisioning a world where Bitcoin is ubiquitous. They imagine a world based on private property (Hoppe's proprietarianism), free-market economics (von Mises' laissez-faire), and more traditional social structures with a return to family or religion, accompanied by increased technological development due to the demise of fiat money or inherently malicious governments. Ultimately, many individuals in the web3 sphere possess a defined vision of the future centered around decentralization, questioning the role of the state, a return to (crypto)tribalism, or other ideas. It is not surprising to see that many futuristic groups, such as adherents of solarpunk, or other ideologies like certain anarchist or religious currents, can resonate with the proposition of Bitcoin.

To my knowledge, there are currently no films focused specifically on Bitcoin or crypto, but that is likely to change in the future. Predecessors of Bitcoin, such as e-gold in 1996, B-money in 1998, and bitgold in 2005, paved the way for the emergence of a true digital hard currency. Many other historical subjects, like the Escuela de Salamanca or the rise of the Austrian School of Economics, could be explored. Speculative fiction related to the fall of the current fiat system and the emergence of an economic system based on Bitcoin could also be explored. This criticism can be extended to the entire crypto ecosystem: with concepts like NFTs, one would have expected a rich subculture unique to cryptos to have emerged. Crypto digital artists, pseudo-anonymous artists, an internet-native culture overall—cryptos seem to lag behind in creating a true counterculture analogous to the hippies of the 1970s.

Culture emerges organically, from the bottom up, so it is difficult to predict in which direction crypto-cinema could go. It took over 20 years to see the rise of native digital artists, with the Soundcloud subculture and artists like Lil B & Lil Peep. This came years after Napster, eMule, and other peer-to-peer architectures characteristic of the early internet. Many groups sought to emulate the early internet and its ideals such as open architecture, peer-to-peer sharing, absence of surveillance, cryptography, etc. and, more broadly, the ethos of crypto-anarchists or cypherpunks, for whom the internet is a place to challenge hierarchical structures like states or corporations. The internet is a space where one can be whoever they want without authorization or permission: in concrete terms, everyone is an IP or MAC address, which does not convey information about the individual behind it. These are pseudonymous systems, and technologies like PGP, onion routing, etc. have made this even more accessible.

Among these projects aiming to revive a new internet with these ideals at the core of its architecture, one can think of Urbit, for example. It is a project that seeks to innovate in its approach to the structure of an operating system while solving the issue of multiple identities on the internet through a unique address called "planets" to identify users. It also provides an environment to develop and operate decentralized applications (dApps). Urbit is a project with a strong culture, deeply rooted in underground references, with its own aesthetics and a community that differs substantially from the traditional world of web3. We can highlight the works of Justin Murphy, for instance, which intersect Landian accelerationism and Deleuzian thought, neoreaction, Christianity, and more. Another example is the Milady NFT project.

In this context, technocryptoptimism encompasses these movements, leveraging their belief in the technical development of cryptocurrencies to advance their own ideas, in opposition to the emerging splinternet controlled by GAFAM or the CCP.

Several other political currents and ideologies have emerged and gained popularity since the early 2000s. Drawing influence from the New Right and the writings of Alain de Benoist in the 1960s, neoreaction (NRx) is a post-conservative philosophy that highlights the inability of the American conservative establishment to offer a solution to their problems and more generally emphasizes a loss of confidence in the American democratic process.

Several groups identify with or can be classified as part of neoreaction. These include the alt-right, a movement that emerged on 4chan in the 2010s, as well as the Dark Enlightenment, a school of thought developed by Curtis Yarvin, who is also a co-founder of the Urbit project. The ideas of the Dark Enlightenment were further developed by Nick Land and challenge the Whig historiography. This historiography is an element of liberal mythology that sees history as a forced march toward a more open, scientific, egalitarian, and free world, aligning with the tenets of liberal democracy. Instead, they value alternative forms of governance, ranging from authoritarian governments like those in the United Arab Emirates or Singapore to absolute monarchy, and even new ideas like neo-cameralism. Neoreaction has authors such as Bronze Age Pervert or Sprandell, who introduced the concept of bioleninism.

An important aspect of certain subcurrents within neoreaction is the emphasis on nature, with a capital "N," perceived as almost an independent entity that needs to be preserved against the great evil of industrialization and its consequences: woke culture, immigration, etc.

It is therefore not surprising that neo-pagan imagery is strongly associated with it. Humanism and its offspring (Marxism, fascism, liberalism) are seen as a direct continuation of the Christian heritage of the West. Taking inspiration from Nietzschean thought, a schism occurs, rejecting Christian values of equality or forgiveness in favor of a more aggressive approach, drawing inspiration from Germanic-Scandinavian culture that gave rise to the Vikings or Nazism. Beyond thinkers-theorists like BAP, these groups are also known for their propensity for violence, even committing acts of terrorism: Anders Breivik in 2011 or Brenton Tarrant, who carried out the Christchurch mosque shootings in 2019, killing 51 Muslims during Friday prayers in New Zealand mosques. The latter openly espoused eco-fascism, an idea he developed in his manifesto.

A resurgence (sometimes mimicked as 'retrvn' in certain underground cultures) of forms of neopaganism is not specific to certain neo-fascist groups but seems to be a broader trend in the post-Christian and post-liberal world.

Christianity and organized religion seem to be waning in the West. Protestant values of freedom and individualism have a much weaker influence on American social life, and this spiritual void is being filled by post-Protestant ideologies, such as wokeism, a term I partially reject because it is actually the logical continuation of Western progressivism. I prefer to call it post-Protestantism, although it may be an abuse of language, as neoreaction also operates within this framework.

Among the commonalities between Protestantism and post-Protestantism, one can note the idea of moral perfectionism, an emphasis on community rather than institutions (similar to American preachers), or Puritan witch hunts. Additionally, they share commonalities in their founding myths and narratives. This is something they share with other humanists, but post-Protestantism is based on a different framework, a post-human framework that sets aside the intrinsic value of the human and its values. It shifts from a subject-oriented ontology to an object-oriented ontology, as seen in Heidegger through deconstruction.

Thus, post-Protestant founding narratives adopt a perspective that places the human in the background. Humanist values are rejected, aligning with paradigms rooted in inequalities, colonization, white supremacism, and speciesism. Christian eschatology, with its idea of the end times, the Antichrist, and the return of the Messiah, is replaced by the notion of an ecological disaster caused by humans through climate change—not problematic for humans per se, but for animals, rivers, and mountains. Like BAP's thinking, the imperative is to protect Nature at all costs, even if it means sacrificing our humanity.

We are witnessing a resurgence of paganism, animism, and their iconography, with an emphasis on the relationship between humans and nature, even though post-Protestant movements do not directly claim them.

For a perspective on the relationship between spirituality, Generation Z, and social media, I invite you to read this article by Esmé Partridge.

In conclusion, culture is a complex domain that intertwines technological, economic, and social development. While it is difficult to predict the direction that culture may take, several trends can be highlighted, such as the cyclic behavior it can exhibit at times, reacting to itself and its own development. It is evident that post-Y2K culture is currently in a plateau, unable to refresh itself due to a lack of a broader vision of the future, thus fixating on an idealized future that is easier to comprehend, instead of constructing a vision of the future that is right in front of us. This is problematic because art and culture play a major role in shaping our fears and desires. A society that does not know its own values or the direction it is heading risks getting lost in desperate attempts to regain its footing. This partially explains the more radical stance that we can observe, for example, in the United States after 2016 and the election of Trump. An unpopular opinion I hold is that the country could experience a civil war in the next few decades, and growing tensions in various regions of the world, Europe being the first.

When fertility rates reach record levels in East Asia, the solution is not necessarily to encourage women to have more children through financial incentives. This approach did not work in Hungary, and I doubt it will work in mainland China. Why? Because it is primarily a cultural issue. China, under Mao, carried out extensive propaganda to encourage households to have only one child, emphasizing the concentration of resources that would enable them to succeed better and generally encouraging young women not to have children in order to have greater physical and social mobility and promote rural exodus. These policies do not change overnight. If China wants to increase its fertility rate, it should promote a culture and a way of life that encourage the idea of having children through cultural production (films, TV series, books, etc.), as well as societal models and celebrities who highlight the benefits of large families, etc. While low fertility rates are just one example among many, as it is conceivable to create a dystopia based on localized or global depopulation, it affects several aspects of society: recycling, water consumption, minority rights/representation, etc. All of these aspects are influenced by cultural and mimetic elements.

Therefore, it is necessary to promote artistic creation in order to create universes that have not yet been conceptualized. The future does not necessarily resemble fiction because there are always unknown areas that we are ignorant of. Think about the unexpected emergence of the Internet, which people still doubted would succeed in 2005, while technologies of that time, such as nuclear power and space industry, were set aside due to a lack of political will. If today we believe that the future lies in CRISPR-Cas9, the technological singularity brought about by the emergence of strong artificial intelligence, nuclear fusion, or quantum computing, perhaps change will come from an area we have ignored or that we are not yet aware of. Maybe we will discover a new use for a material, a new way to produce food, or an innovation in the field of information technology that will completely change our contemporary technical and scientific paradigm.

But creating fiction remains positive as it reinforces some of our beliefs and expands our horizons, creativity, and ultimately our ability to act on the material world. We need more books, more films, more concepts. We need to accelerate the production of ideas. However, not just easy ideas or concepts characteristic of our fiat era, but ideas capable of bringing about major cultural changes.